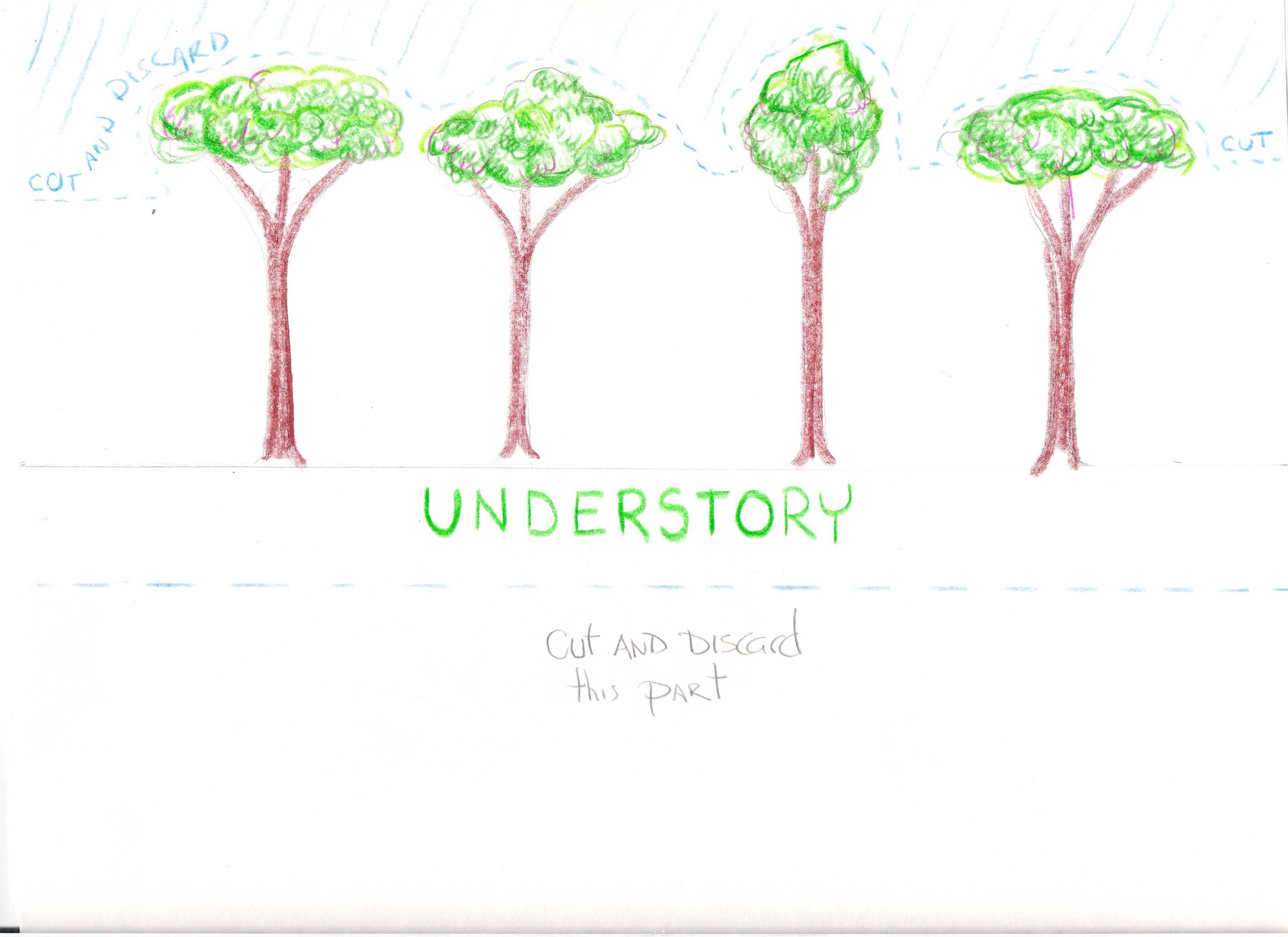

UNDER

STORY

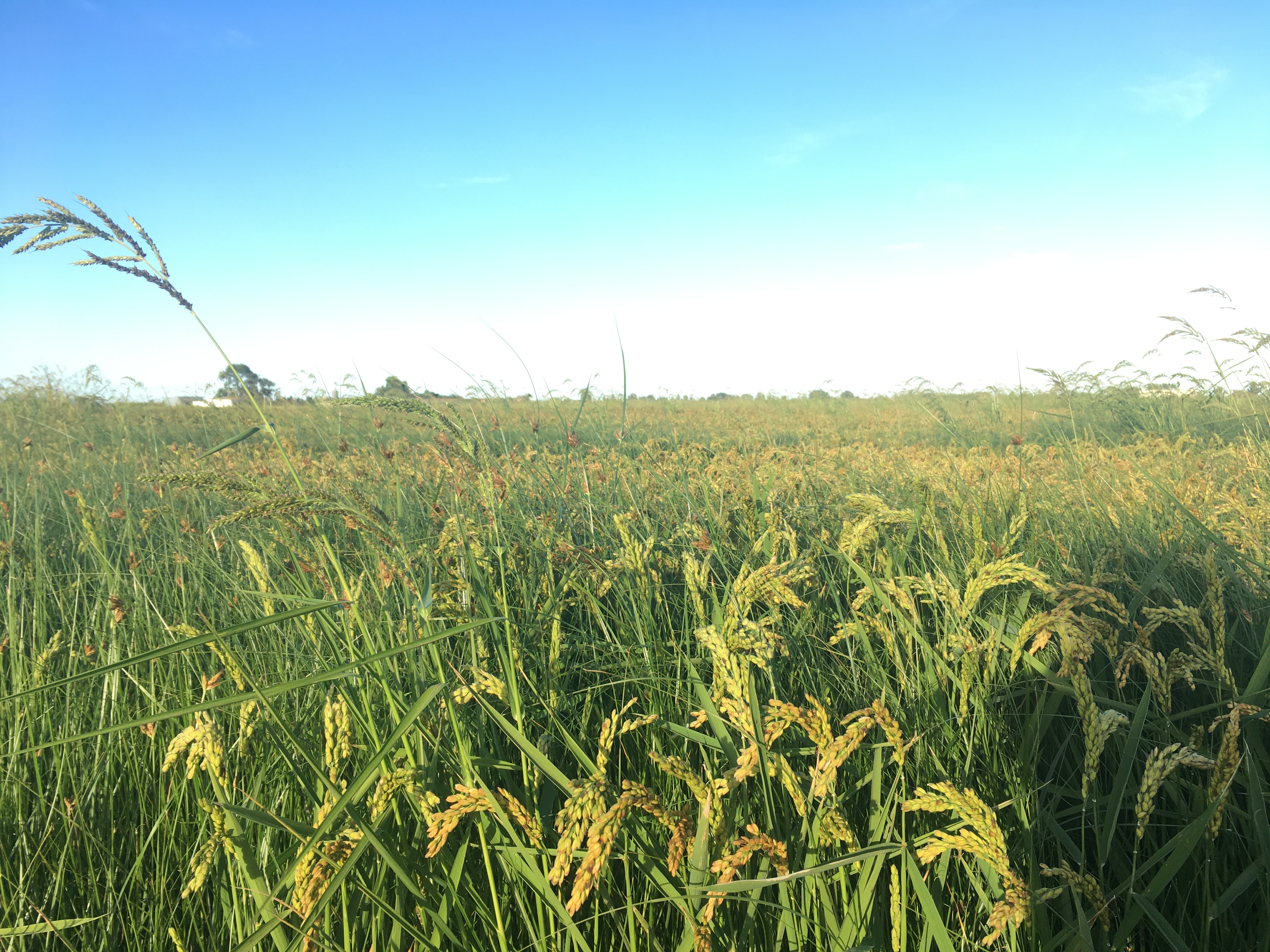

All the colours of rust and sunset, brown-reds and pale greens, changed ceaselessly in the long leaves as the wind blew. The roots of the copper willows, thick and ridged, were moss-green down by the running water, which like the wind moved slowly with many soft eddies and seeming pauses, held back by rocks, roots, hanging and fallen leaves. No way was clear, no light unbroken, in the forest. Into wind, water, sunlight, starlight, there always entered leaf and branch, bole and root, the shadowy, the complex. Little paths ran under the branches, around the boles, over the roots; they did not go straight, but yielded to every obstacle, devious as nerves. The ground was not dry and solid but damp and rather springy, product of the collaboration of living things with the long, elaborate death of leaves and trees; and from that rich graveyard grew ninety-foot trees, and tiny mushrooms that sprouted in circles half an inch across. The smell of the air was subtle, various, and sweet. The view was never long, unless looking up through the branches you caught sight of the stars. Nothing was pure, dry, arid, plain. Revelation was lacking. There was no seeing everything at once: no certainty. The colours of rust and sunset kept changing in the hanging leaves of the copper willows, and you could not say even whether the leaves of the willows were brownish-red, or reddish-green, or green.

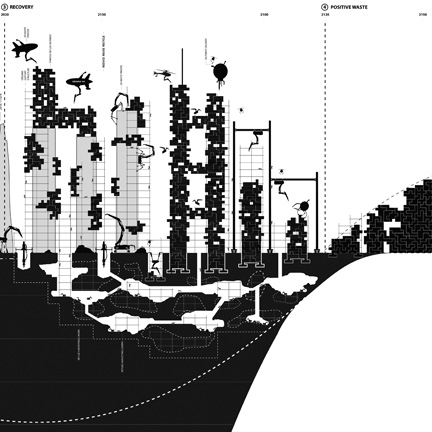

Today a new word has been created to characterize our situation: our epoch would be the epoch of the anthropocene. One need not be paranoid in order to ask oneself if the success of this word, as much in the media as in the academic world (in a few years the number of conferences and publications on the anthropocene has exploded), doesn’t signal a transition from the first phase—of denial—to the second phase—that of the new grand narrative in which Man becomes conscious of the fact that his activities transform the earth at the global scale of geology, and that he must therefore take responsibility for the future of the planet. Of course, many of those who have taken up this word are full of goodwill. But Man here is a troubling abstraction. The moment when this Man will be called on to mobilize in order to “save the planet,” with all the technoscientific resources that will be “unhappily necessary,” is not far off.

Isabelle Strengers

EN AQUESTA NOVA ERA JA NO ENS ENFRONTEM NOMÉS A UNA NATURA QUE HEM DE “PROTEGIR” DEL DANY CAUSAT PELS HUMANS, SINÓ TAMBÉ AMB UNA NATURA CAPAÇ D’AFECTAR GREUMENT ELS NOSTRES CONEIXEMENTS I MANERES DE VIURE

CLICK ON ME!

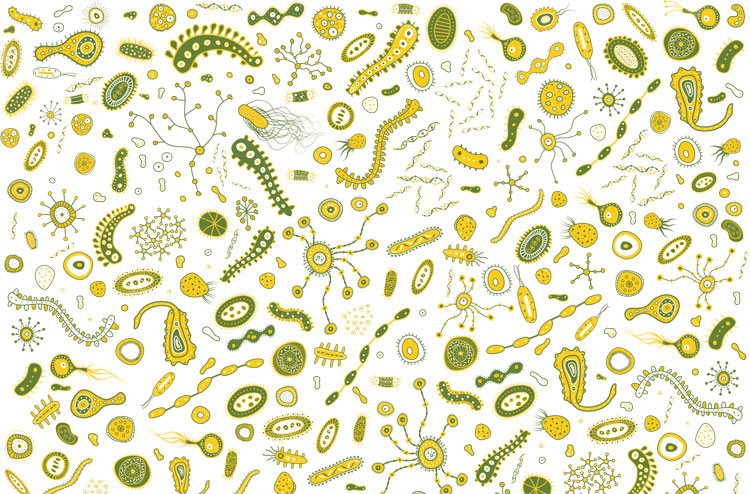

Everywhere we go, our microbiome interacts with the microbiomes of new environments and of the people we meet

El poder actual no se define por sus instituciones políticas, sino por sus infraestructuras. Es arquitectónico, más que representativo.

Comité invisible

Cada pedazo de la economía y el ámbito social está ya investido de estos mecanismos de proyecto, de medida, de control. ¿No es lo que se conoce como "ingeniería social"? Es decir, la penetración de todas las esferas de la actividad humana por las armas del administrador, que actúa a golpe de regulación y, después, de buldócer y gas lacrimógeno. (...) Hoy en día todo gobierno no es tanto un gobierno político como un gobierno de proyectos. Y, tarde o temprano, silban las pelotas de goma.

Jean-Baptiste Vidalou

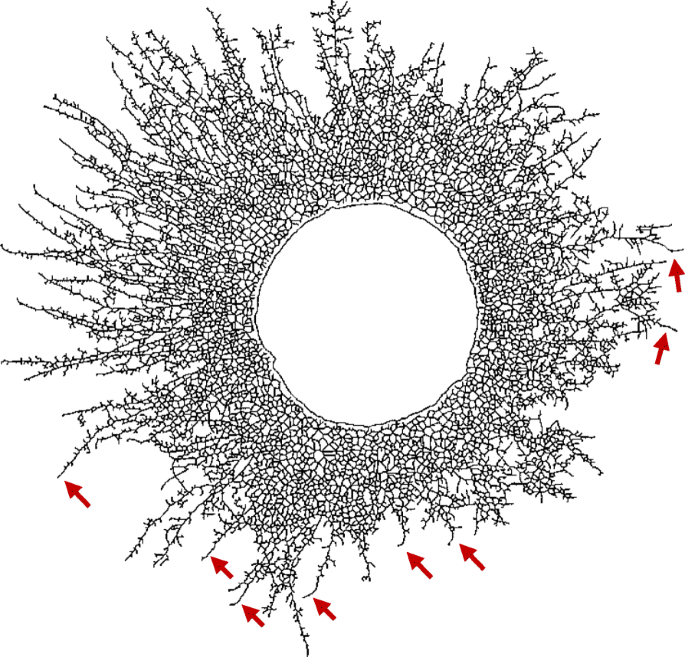

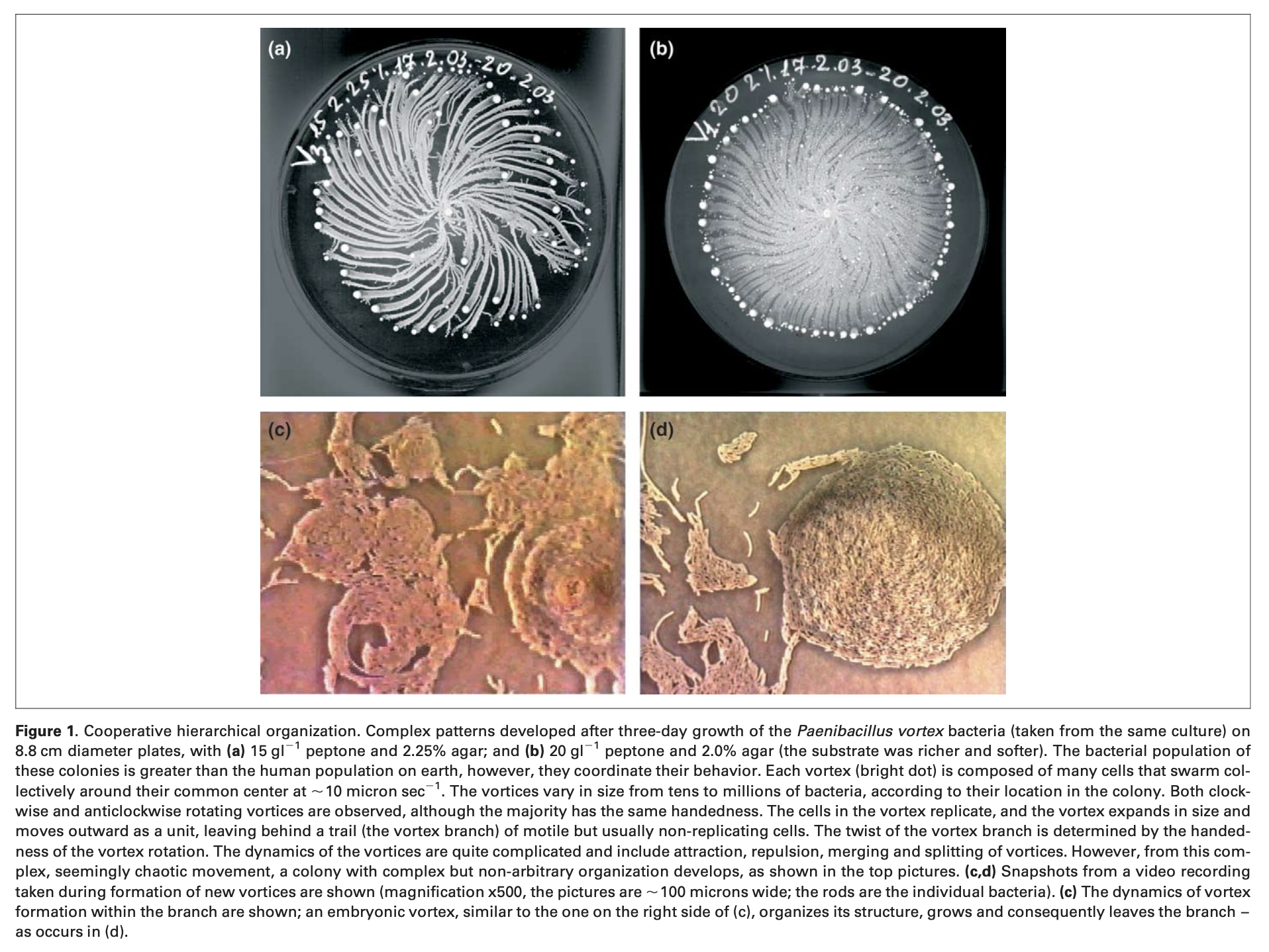

To come to grips with this phenomenology, we turn to the field of linguistics, the metaphors of which have already begun to penetrate the description of bacterial communication. Usually, these metaphors refer to the structural (lexical and syntactic) linguistic motifs. Here, we reason that bacterial chemical conversations also include assignment of contextual meaning to words and sentences (semantic) and conduction of dialogue (pragmatic) – the fundamental aspects of linguistic communication. Using these advanced linguistic capabilities, bacteria can lead rich social lives for the group benefit. They can develop collective memory, use and generate common knowledge, develop group identity, recognize the identity of other colonies, learn from experience to improve themselves, and engage in group decision-making, an additional surprising social conduct that amounts to what should most appropriately be dubbed as social intelligence.

Eshel Ben Jacob, Israela Becker, Yoash Shapira, Herbert Levine

One example of the advantage of bacterial discourse is the starvation response of many species. When growth conditions become too stressful, bacteria can transform themselves into inert enduring spores. Sporulation is a process executed collectively and beginning only after ‘consultation’ and assessment of the colonial stress as a whole by the individual bacteria. Simply put, starved cells emit chemical messages to convey their stress. Each of the other bacteria uses the information for contextual interpretation of the state of the colony relative to its own situation. Accordingly, each of the cells decides to send a message for or against sporulation. Once all of the colony members have sent out their decisions and read all other messages, sporulation occurs if the ‘majority vote’ is in favor.

Both in forest and in science, spores open our imaginations to another cosmopolitan topology

Anna Tsing

Spores take off toward unknown destinations, mate across types, and, at least occasionally, give rise to new organisms -a beginning for new kinds. In thinking about landscapes, spores guide us to in-population heterogeneity.

Like most Terrans on Terra, Lyubov had never walked among wild trees at all, never seen a wood larger than a city block. At first on Athshe he had felt oppressed and uneasy in the forest, stiffed by its endless crowd and incoherence of trunks, branches, leaves in the perpetual greenish or brownish twilight. The mass and jumble of various competitive lives all pushing and swelling outwards and upwards towards light, the silence made up of many little meaningless noises, the total vegetable indifference to the presence of mind, all this had troubled him, and like the others he had kept to clearings and to the beach.

Benvingudes a Understory.

Ens trobem a 152 metres sobre el nivell del mar, amb una temperatura atmosfèrica de 23 graus i un 12% d’humitat. Ara mateix, el conglomerat urbà de Barcelona ocupa l’espectre sonor formant una antropofonia constant d’entre 30 i 65 decibels.

Esteu a punt de sentir els sons d’un altre món.

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

It just so happens that the upland border area we have chosen to call Zomia represents one of the world’s longest-standing and largest refuges of populations who live in the shadow of states but who have not yet been fully incorporated. (...) I have come to see this study of Zomia, or the massif, not so much as a study of hill peoples per se but as a fragment of what might properly be considered a global history of populations trying to avoid, or having been extruded by, the state. (...) Aside from being located in remote, marginal areas that are difficult of access, such peoples are also likely to have developed subsistence routines that maximize dispersion, mobility, and resistance to appropriation. Their social structure as well is likely to favor dispersion, fission, and reformulation and to present to the outside world a kind of formlessness that offers no obvious institutional point of entry for would-be projects of unified rule. Finally, many, but by no means all, groups in extrastate space appear to have strong, even fierce, traditions of egalitarianism and autonomy both at the village and familial level that represent an effective barrier to tyranny and permanent hierarchy.

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed. An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

Making maps is hard, but mapping Guizhou province especially so... The land in southern Guizhou has fragmented and confused boundaries... A department or a county may be split into several subsections, in many instances separated by other departments or counties.... There are also regions of no man’s land where

the Miao live intermixed with the Chinese... Southern Guizhou has a multitude of mountain peaks. They are jumbled together, without any plains or marshes to space them out, or rivers or water courses to put limits to them. They are vexingly numerous and ill-disciplined. Very few people dwell among them, and generally the peaks do not have names. Their configurations are difficult to discern clearly, ridges and summits seeming to be the same. Those who give an account of the arterial pattern of the mountains are thus obliged to speak at length. In some cases, to describe a few kilometers of ramifications needs a pile of documentation, and dealing with the main line of a day’s march takes a sequence of chapters.

As to the confusion of the local patois, in the space of fifty kilometers a river may have fifty names and an encampment covering a kilometer and a half may have three designations. Such is the unreliability of the nomenclature.

Guiyang Prefectural Gazetteer, 1850

The hilly and jungly tracts were those in which the dacoits held out longest. Such were [sic] the country between Minbu and Thayetmyo and the terai [swampy lowland belt] at the foot of the Shan Hills and the Arakan and Chin Hills. Here pursuit was impossible. The tracts are narrow and tortuous and admirably suited for ambuscades. Except by the regular paths there were hardly any means of approach; the jungle malaria was fatal to our troops; a column could only penetrate the jungle and move on. The villages are small and far between; they are generally compact and surrounded by dense, impenetrable jungle. The paths were either just broad enough for a cart, or very narrow, and, where they led through the jungle were overhung with brambles and thorny creepers. A good deal of the dry grass is burned in March, but as soon as the rains recommence the whole once more becomes impassible.

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, 1893

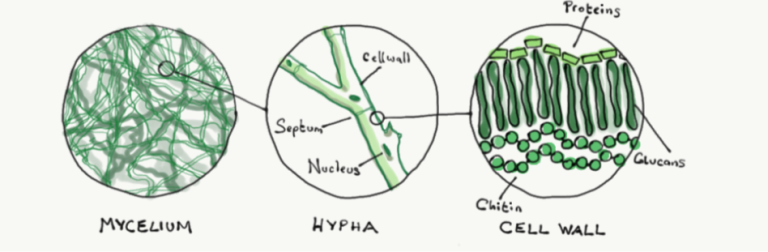

Whenever communities form, communication is necessary and collaboration inevitable. Mycelial networks, ecosystems, and human societies all exhibit this rule of Nature through their shared dependence on participation and symbiosis.

Peter McCoy, Radical Mycology

To appreciate polyphony one must listen both to the separate melody lines and their coming together in unexpected moments of harmony and dissonance. In just this way, to appreciate the assemblage, one must attend to its separate ways of being at the same time as watching how they come toguether in sporadic but consequential coordination.

The polyphony of the assemblage shifts as conditions change.

Anna Tsing

Implied in this elusive connectivity is a concept underlying the field of chaos theory: because each act carries an unknown and immeasurable potential, objects and their interactions are essentially impossible to thoroughly describe. The result is that our descriptions of the world must be recognized as mental constructs, primarily created to make sense of the universe's unintelligible and infinite chaos.

Peter McCoy, Radical Mycology

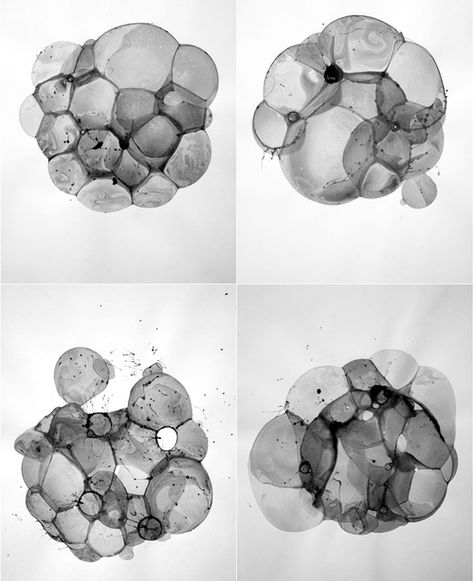

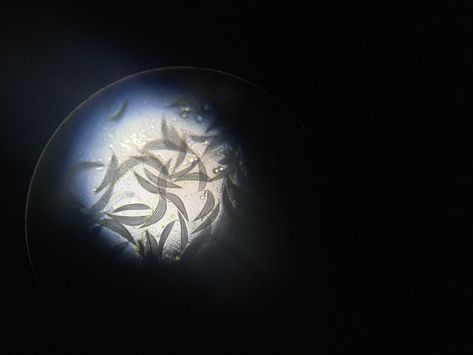

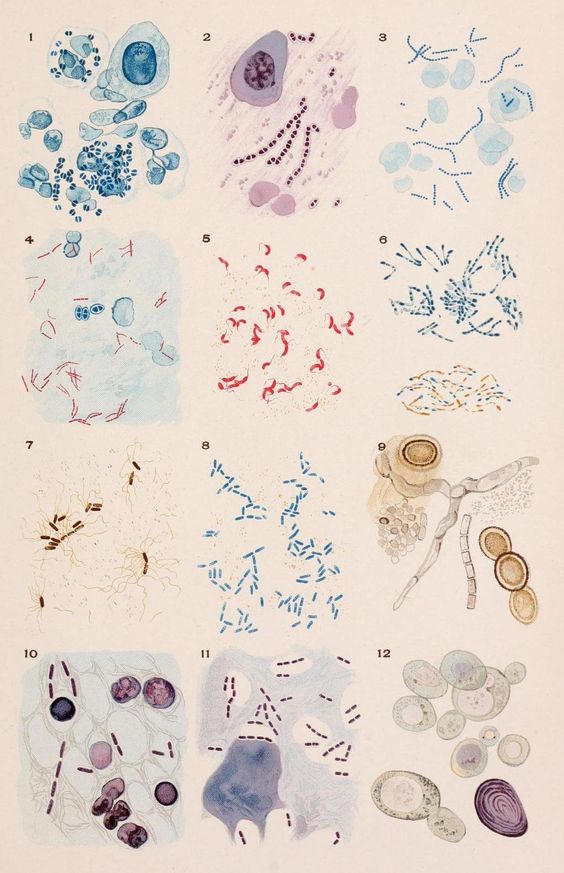

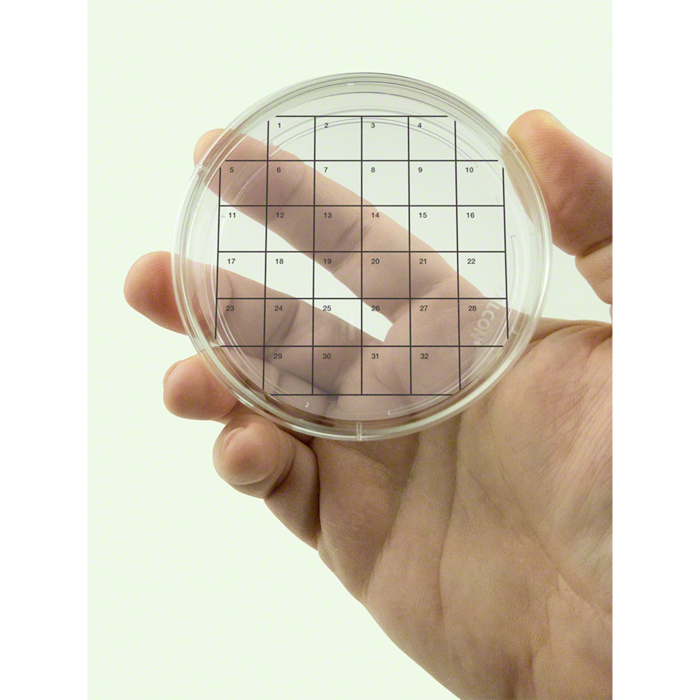

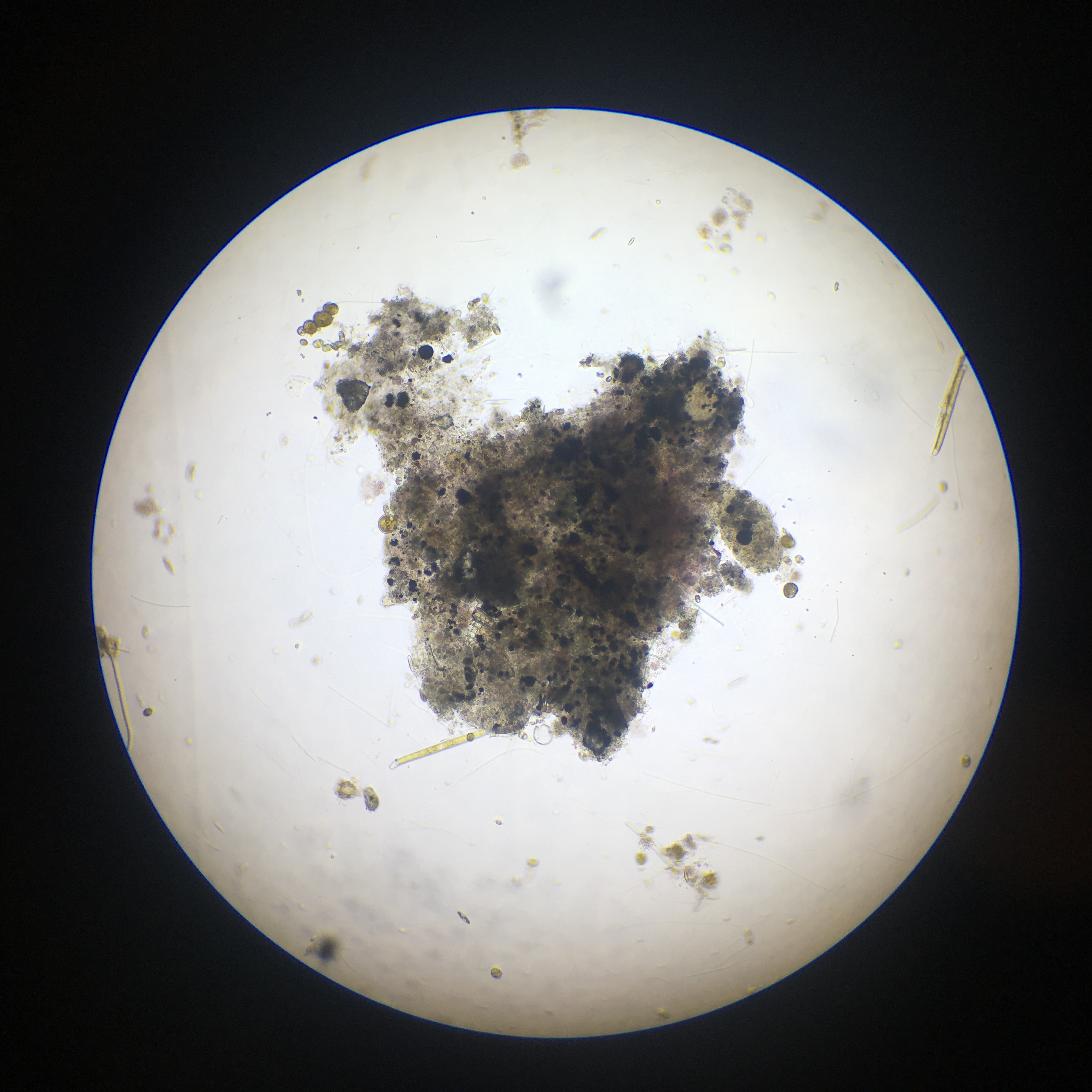

Observació #8 Delta de l'Ebre

Microscopi x400

The genetic apparatus of the fungus is open-ended, able to add new material.

In fungal mosaics, each cell line can sense the others, forming mushrooms in unison. By examining fungi differently, a new object came into sight: the genetic diverse fungal body, the mosaic.

Anna Tsing

Observació #8 Delta de l'Ebre

Microscopi x400

Observació #23 Delta de l'Ebre

Microscopi x100

Observació #12 Delta de l'Ebre

Microscopi x400

ISABELLE STENGERS

Vivim en temps estranys, una mica com si ens trobéssim suspeses entre dues històries, totes dues relacionades amb un món que s'ha fet "global". La primera ens és familiar: avança al ritme del progrés, impulsada per la competitivitat mundial i amb el creixement econòmic com a vector temporal. No deixa cap mena de dubte pel que fa al que necessita i al que promou, però es caracteritza per una indefinició considerable pel que fa a les seves conseqüències. La segona història, en canvi, ens confronta amb bastanta claredat amb el que està passant, però és absolutament opaca a l'hora de saber què necessita, com podem respondre al que està passant.

Isabelle Stengers, In Catastrophic Times

A The Word for World is Forest, Ursula K. Le Guin descriu el Món 41, un planeta-colònia a 27 anys llum de distància de la Terra. El Món 41 està completament cobert de boscos, plantats per éssers humans milers d’anys abans, per explotar-los en el futur com a matèries primes, en un moment en què la Terra ha quedat completament desproveïda de vegetació. Al Món 41, els colons terrans han de conviure amb una població nativa, uns humans coberts de pèl verd i de poc més d’un metre d’alçada els quals els terrans utilitzen com a mà d’obra esclava i anomenen, despectivament, “creechies”. Evidentment, els terrans es neguen a reconèixer els creechies com a humans, i el bosc com el seu hàbitat.

One example of the advantage of bacterial discourse is the starvation response of many species. When growth conditions become too stressful, bacteria can transform themselves into inert enduring spores. Sporulation is a process executed collectively and beginning only after ‘consultation’ and assessment of the colonial stress as a whole by the individual bacteria. Simply put, starved cells emit chemical messages to convey their stress. Each of the other bacteria uses the information for contextual interpretation of the state of the colony relative to its own situation. Accordingly, each of the cells decides to send a message for or against sporulation. Once all of the colony members have sent out their decisions and read all other messages, sporulation occurs if the ‘majority vote’ is in favor.